On Monday, our Smart Options advisory service entered into two new debit spreads… the newsletter's primary type of trade. In that a debit spread is the next natural progression of simple purchases of puts and calls yet still seems to vex some traders, a closer look at one of the trades and the thought process behind it would be time well spent.

A debit spread is a type of vertical spread, meaning contains two calls with the same expiration but different strikes. One is bought and the other is sold. The strike price of the option being shorted is higher than the strike of the option being bought, which means this strategy will always require an initial outlay, or debit.

In simpler but perhaps more meaningful terms, a debit spread is the outright purchase of a put or a call and is therefore a directional bet. But, the total expense of that trade's entry is partially offset by collecting proceeds from the sale of the same kind of contract but with a different strike price.

In this particular example, the Smart Options service bought Microsoft (MSFT) June Week 4 (06/23) 67 calls (MSFT 170623C67) at $3.76, or $376 per contract. And, we simultaneously sold — or shorted — the Microsoft (MSFT) June Week 4 (06/23) 71 calls (MSFT 170623C71) at $0.60 or $60 per contract. The net cost, or debit, was $3.16 for this debit spread, which means we had to shell out $316 for every pair of contracts we took on.

This is a bullish position, meaning we expect Microsoft shares to move higher; the plan is to exit both of the above-mentioned positioned for a credit in excess of our cost, or debit. That's what the purchase of the 67 call does. The sale of the 71 call just puts a little cash back on our pocket to reduce our total at-risk capital. And, note that in our case the strike price of the call we shorted is above the stock's current price. It doesn't have to be that way, but that's usually the optimal way to do it. Conversely, the strike price of the call we're buying is rather well below the stock's current price.

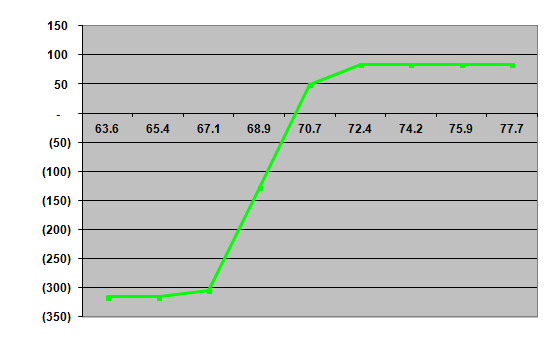

Note that both options together establish a floor and a ceiling for our trade. The most we can lose on this trade is our $316 debit, which would only happen if Microsoft stagnates or sinks. Our maximum potential gain here is $0.84, or $84 per pair of contracts. The profit-and-loss chart below walks us through the possible scenarios of this particular debit spread (assuming we were making our exit on expiration day).

That doesn't seem like a whole lot of reward compared to the potential loss. But, the odds of realizing the maximum loss is actually pretty thin. Even a modestly bullish move would close the gap on our favor pretty quickly. At $72, MSFT would already have given us our maximum gain. And, Microsoft shares would have to be below $66.35 for us to realize that maximum loss. Even if Microsoft was at $68.88 on expiration day, we could still get out of the trade [by buying the short and selling the long] and only book a total loss of $128 on the trade.

Just to better illustrate exactly what's going on here though, let's break out the various potential values of each leg of the debit spread on a profit and loss chart.

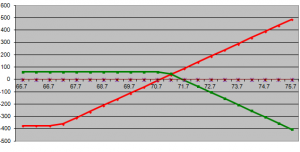

That's what we've got below. The long call's value is plotted in red along the spectrum of all the potential prices for MSFT shares, and the short call's net value (to us) is plotted in green. [Again, this is what the prices would be upon expiration. The graphic changes slightly every day leading up to the expiration date of June 23rd.]

As you can see, the call we outright own is 100% subject to the price of MSFT. The call we shorted, which was the 71 call, only does us any good as long as MSFT is below $71. Once Microsoft shares are above $71 then the call increasingly becomes more likely to be exercised against us. Any price above $71.63 and not only is the call exercised against us, but the cost of that exercise starts to eat into the initial credit of $0.60 we got for selling the call. (In fact, that green P&L line for the $71 call crosses under the zero mark at $71.60.)

Of course, as long as MSFT shares are above $70.50 or so at expiration, we're roughly going to break even by exiting the entire debit spread for about our initial cost, or debit.

Remember, the profit (or loss) we book on this particular trade will always be the midpoint between the green line for the $71 calls and the red line for the $67 calls we own. That midpoint is above zero as long as Microsoft is above $70.50, and that midpoint is below zero when Microsoft shares are under $70.50 right before expiration day.

Hopefully this example walks you through the strategy and thought process behind a call debit spread; that short call is mostly just a way of offsetting some risk. Without it (and you don't have to have it), these trades are just like the outright purchase of a call or put. That offset in price, however, puts a floor and a ceiling on these trades.

The best way to learn more about these call debit spreads is to do a few of them on a hypothetical basis, or paper trading. That way you'll be able to get a better feel for which options to trade, and how much time to buy.

Or, if you're looking for specific debit spread trading suggestions, many Smart Options subscribers report learning a great deal about how they work just be receiving our newsletter alerts. Go here to learn more about the service.