The Ratio Of Dividend Yields To Bond Yields In Historical Perspective

1959 all over again? Why this could be another historic moment for the market

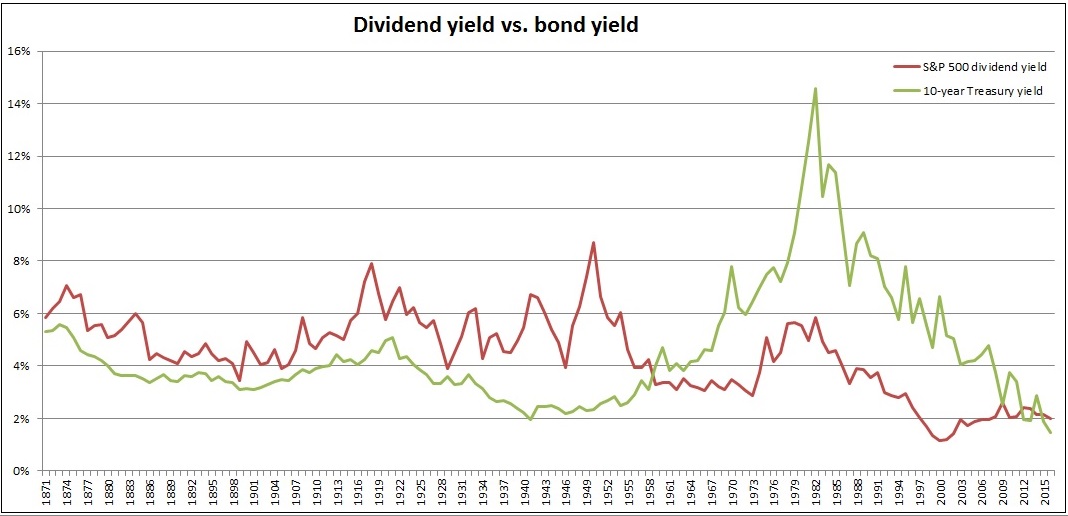

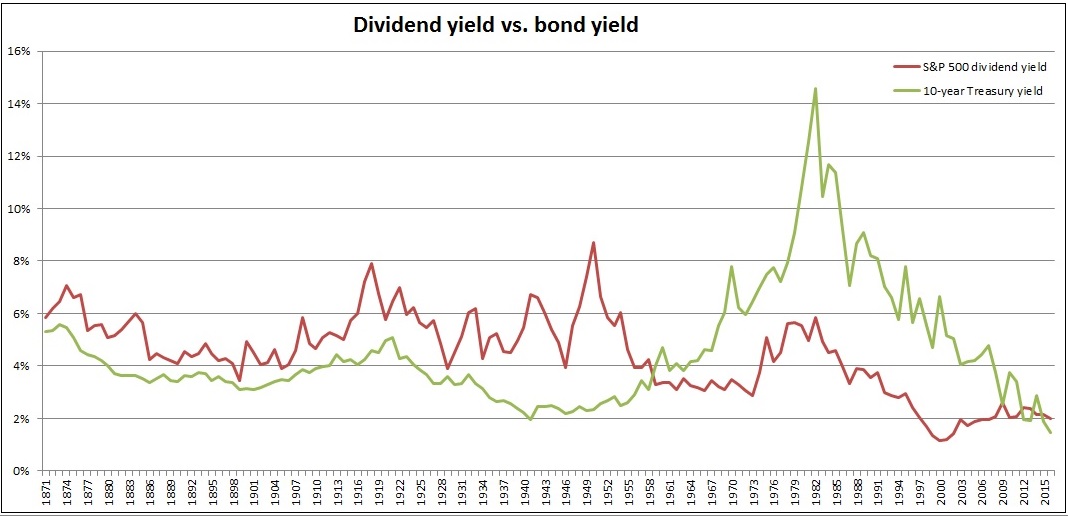

In the history of yield-seeking investments, 1959 was a seminal year — the one in which bond yields and dividend yields flipped. The question investors must now contend with is whether they have finally flipped back.

It may not be one of those years that has widespread recognition among armchair market historians, such as 1929 or 1999, but 1959 was a critical one nonetheless. Before 1959, dividend yields on stocks were reliably above those of bonds. This made all the sense in the world insofar as stocks were seen as a riskier way to generate income; since they don't come with the legal obligations that adhered to bond payments, dividend yields had to be higher as compensation for risk.

This is the simple explanation for the fact that whenever dividend yields slid to approach bond yields, as they did in 1898 and 1929, stock prices fell or bond prices rose such that the relationship between the one type of yield and the other was maintained.

It is no surprise, then, that when dividend yields approached bond yields again and actually rose above them in 1959, the old Wall Street hands had a clear prediction of what would happen.

As Peter Bernstein tells it in his classic book "Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk":

my partners, veterans of the Great Crash, kept assuring me that the seeming trend was nothing but an aberration. They promised me that matters would revert to normal in just a few months, that stock prices would fall and bond prices would rally.

I am still waiting. The fact that something so unthinkable could occur has had a lasting impact on my view of life and on investing in particular. It continues to color my attitude toward the future and has left me skeptical about the wisdom of extrapolating from the past.

That is to say, instead of reversing, bond yields rose dramatically above dividend yields — and by 1982, the 10-year Treasury yield was nearly 9 percent higher than the S&P's dividend payout. In hindsight, 1959 marked an epic sea change, as the below chart (which uses data from Yale's Robert Shiller) shows:

Interestingly, opinions on what drove the shift are divided.

Bernstein's own explanation is that rising inflation amid World War II led the fixed return offered by bonds to be perceived as risky (since inflation increases the chance that the money returned would purchase less than the money lent), driving investors into stocks, which generally compensate investors for inflation (since increases in prices are typically passed along to customers).

Yet Martin Fridson, who wrote about the flip in his own book "It Was a Very Good Year: Extraordinary Moments in Stock Market History," argued to CNBC that there had to have been more at work, given that inflation had also been high in the past.

For Richard Sylla, the Henry Kaufman professor of the history of financial institutions and markets at NYU's Stern School of Business, the late '50s change actually stemmed from events that followed the 1929 stock market crash.

The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 dramatically increased the information that companies and stock dealers had to provide to investors. This reduced the risk premium accorded to stocks, and it allowed advocates like William Greenough of TIAA to make the case that equities belonged in long-term portfolios, given that investors could make informed decisions about which stocks to buy, Sylla argues.

Further, the shift to earnings reports meant that investors could view earnings growth, rather than simple dividend growth, as a key component of future returns. This meant earnings were increasingly reinvested in the businesses rather than doled out as dividends, Sylla wrote in an email to CNBC.

Yet whether increased disclosure or increased inflation anxiety led to the great switcheroo of 1959, it's hard to argue with the lesson Bernstein draws: The past is an insufficient vehicle for predicting the future, and those who blindly bet on regression to the mean are fools with whom their money will soon be parted.

Which brings us to the present. More than one financial commentator has noted the oddity that the S&P 500 now yields significantly more than the 10-year Treasury note; many have gone a step further and argued that this is the most salient case for increasing exposure to stocks now.

Could it be that those making this argument are making the same mistake Bernstein's colleagues were back in 1959 — predicting a Harding-esqe "return to normalcy" when the world has fundamentally changed? For instance, could it be that in a stagnating global economic environment, in which deflation is often a greater concern than inflation, the more-guaranteed return of fixed income merits a premium for this asset class once again? Twenty years hence, will the investors who buy stocks now in anticipation of lower yields through higher prices still be waiting?

"It's very vital to ask this question right now," as the recent shift in dividend yields and bond yields is "tectonic, potentially," Max Wolff of Manhattan Venture Partners said Wednesday on CNBC's "Trading Nation."

Still, he argues that the recent trend is not driven by sentiment, but by central bank actions driving down bond yields, and for that reason he doesn't think the change will endure.

A similar sentiment is echoed by most other market participants. As Fridson, who is also chief investment officer of income-centric wealth management fund Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors, put it: "While you've got stock yields where they are, maybe the reason that they're currently above bond yields is simply that the bond yields have been driven down to levels that don't make sense given the economic fundamentals. That is something we shouldn't expect to continue."

These voices of reason certainly have a point. To be sure, unlike in the late '50s, the current crossing of stock and bond yields appears to have been driven quite solidly by the dramatic decrease in the latter, which may suggest that something specific to the bond market might be at work.

Still, for those who expect everything to return to its prior state, the ghosts of 1959 must still be contended with — not only in respect to bond yields and dividend yields, but when it comes to every facet of our financial world.

Courtesy of cnbc.com